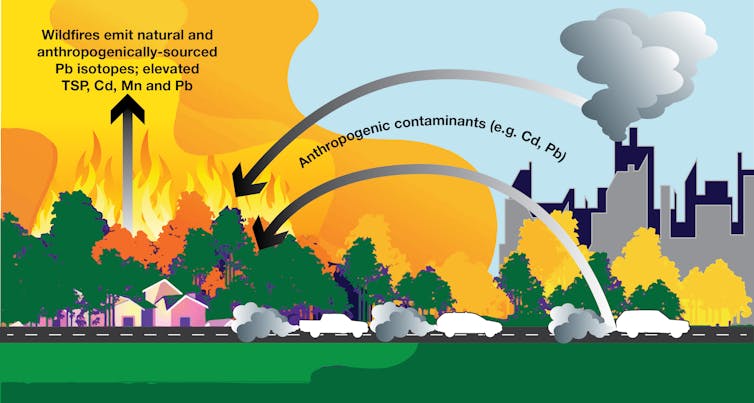

We know forests absorb carbon dioxide, but, like a sponge, they also soak up years of pollutants from human activity. When bushfires strike, these pollutants are re-released into the air with smoke and ash.

Republished from The Conversation by Cynthia Faye Isley and Mark Patrick Taylor

Our new research examined air samples from four major bushfires near Sydney between 1984 and 2004. We found traces of potentially toxic metals sourced from the city’s air — lead, cadmium and manganese — among the fine particles of soil and burnt vegetation in bushfire smoke.

These trace metals were associated with leaded petrol — which hasn’t been used since 2002 — and industrial emissions, which include past metal processing, fossil fuel burning, refineries, transport and power generation.

Recommended: How to Eliminate IBS, IBD, Leaky Gut

This means bushfires, such as the those that devastated Australia last summer, can remobilise pollutants we’ve long phased out. The health and other effects may not be fully understood or realised for decades.

Analysing air samples

We chose four major bushfires — which occurred in 1984, 1987, 2001-2002 and 2004 — because of their known impact on air quality across Sydney. The New South Wales government collected air samples every sixth day on filters over that period and archived them, which meant we could study them years later.

We analysed these air samples during the bushfire periods and compared them to the months either side of each event.

Read more: California is on fire. From across the Pacific, Australians watch on and buckle up

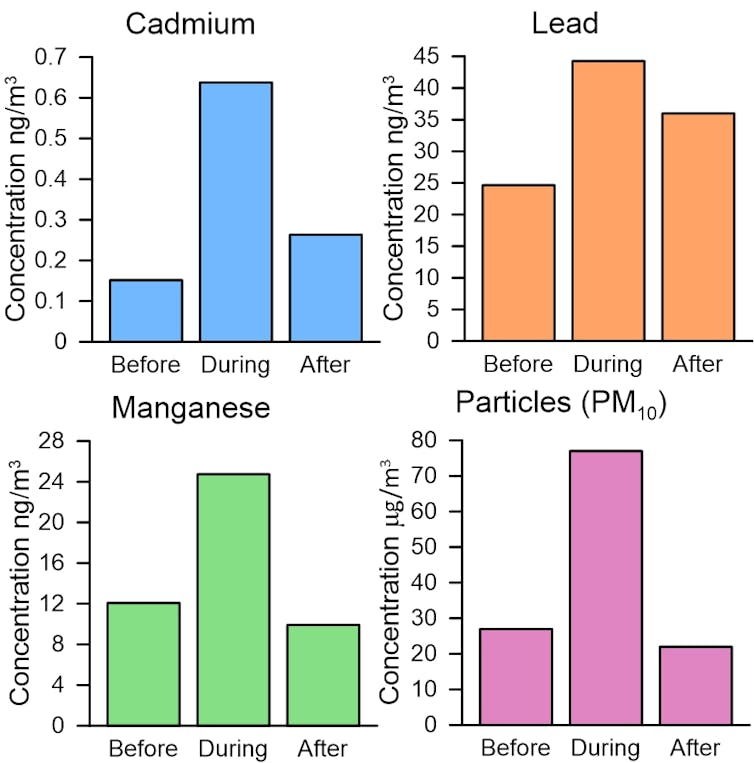

As expected, air pollution levels were higher during bushfires periods, in terms of total suspended particles and fine particles (“PM10”, which are particles 10 microns or less in size).

Using statistical analyses, we separated the source components of the particles: those from natural soils and those originating from human-sourced pollutants. We found the concentration of the human-sourced pollutant component — containing lead and cadmium — doubled during bushfire periods.

Pollution of the air with cadmium is associated with mining, refining, burning fossil fuels, and even from household wastes. But the source of lead pollution has a more complicated story.

A story written in lead

Isotopes are variants of an element, such as lead. Different lead “isotopes” have different atomic masses.

Our study measured lead isotopes in the air samples to “fingerprint” the pollution sources.

The data show that the source of the lead ranges from natural origins derived from the weathering of rocks to those from leaded petrol emissions.

Read more: Explainer: what is an isotope?

Leaded petrol started being phased out in 1985 due to environmental and health concerns, and hasn’t been used in vehicles since 2002. Much smaller amounts are still used in AVGAS — the fuel used to power small piston aircraft engines.

Related: How to Detox From Plastics and Other Endocrine Disruptors

As a result, lead levels in Sydney’s air decreased dramatically from 1984 to 2004. At the same time, the lead isotopes in the air changed.

The lead used in NSW petrol predominantly came from the mines at Broken Hill. Broken Hill lead has a very different isotopic signature to the lead found in Sydney’s main bedrock, Hawkesbury Sandstone. This corresponds to previous research showing ash from Sydney trees contained Broken Hill lead.

In 1994, lead in Sydney’s air was closer to the Broken Hill lead signature. By 2004, the lead isotopes in air resembled natural Sydney rocks. But during bushfires in 2001-2002 and 2004, the lead that was released started to look more like Broken Hill lead again.

This shows that the forests had absorbed leaded petrol emissions over the 70 years it was used and stored them. When the forests went up in flames, the lead was remobilised along with smoke and other bushfire particles.

What does that mean for our health?

Breathing in bushfire smoke is a serious health risk. Bushfire smoke resulted in more than 400 excess deaths during the devastating 2019-2020 bushfires.

Recently, the focus of air quality and health research has shifted to very fine particles: “PM2.5”. These are particles 2.5 microns or smaller that can penetrate deep into our lungs. During the Black Summer bushfires of 2019-2020, PM2.5 levels reached 85 micrograms per cubic metre of air over 24-hours, more than three times the Australian air quality criteria of 25 micrograms per cubic metre.

While our study shows that potentially toxic metals were more elevated in the atmosphere during bushfires, the concentrations were not likely to be a health risk. The main risk is from the total concentration of fine particles in the air, rather than what they are made of.

The concentrations of the trace metals measured during the four major bushfires in our study were below Australian and World Health Organisation criteria. The period of increased exposure was also very limited, further reducing risk.

Nevertheless, it’s important to minimise exposure to all chemical contaminants. This is because many, such as lead, have no safe lower exposure limit and the effects are often proportionately greater at the first and lowest exposure levels.

A lingering legacy

It’s not just Australian forests that have a lingering toxic legacy. In Ukraine and Belarus, radioactive materials from Chernobyl have been released during bushfires.

And as global knowledge of the damaging effects of pesticides grew, we stopped using them. Yet we still find them far from civilisation in the frozen Arctic, waiting to be released when the ice melts.

Metals such as lead, copper, manganese and uranium continue to be mined and processed in Australia. The most significant environmental and health impactsare felt by the immediately surrounding communities, particularly children, as contaminants in the air deposit on surfaces and are later ingested.https://www.youtube.com/embed/zEgLPiFKVm8?wmode=transparent&start=0

Globally, the recycling of lead batteries continues to contaminate communities and environments, particularly those in low to middle income countries.

Yes, our modern lifestyles depend on these metals and other toxic chemicals. So, we must mine, use and dispose of them with great care, because once in the environment, they do not go away.

Read more: How bushfires and rain turned our waterways into ‘cake mix’, and what we can do about it